Salvaged Materials

By Kaushik Shrinivas

Abode for elderly - Oor

The practice of single use of materials has dominated man’s life for a considerable time. It has now been shaken by climate change and resource depletion. It becomes imperative that we realize that we live in a finite world with finite resources where ‘use and throw’ models of consumption just don’t work. While there is an acceptance now of the idea of ‘reuse’, executing it requires imagination and creativity.

While we narrow down to the building sector, we realise that we not only consume over 40% of the overall energy produced in the world but also contribute to tonnes of construction waste. Could construction waste be one of the most sustainable building materials if we just learn how to use it? This was the spark that ignited the project - ‘Oor - Abraham’s Homeland’

Conceptualized as an abode for the elderly who are in need of a home, ‘Oor - Abraham’s Homeland’ is located in the Pathanamtitta district of Kerala. The owner of the project - Abraham envisioned to give a second life to the elderly whose worth is often overlooked. To symbolize the project’s intent, even the abode was decided to be built almost entirely using materials salvaged from old buildings, which in a sense aims to give a second life to these materials and re-establish their worth. It was with this idea that Abraham approached COSTFORD to realize his dream project, who with their expertise helped him design and construct ‘Oor’. Given below is the list of construction materials which have been reused.

1. Re-using Mud as Cob

One of the primary materials used in the project was mud. There was a lot of scope of salvaging building quality mud as they were extensively used in the old buildings of Kerala. In Abraham’s Oor, we see two specific building technologies with mud. One is cob, which is basically clay modelling for starters where ovoid or cylindrical units of mud are taken and smashed in place over one another to construct a wall.

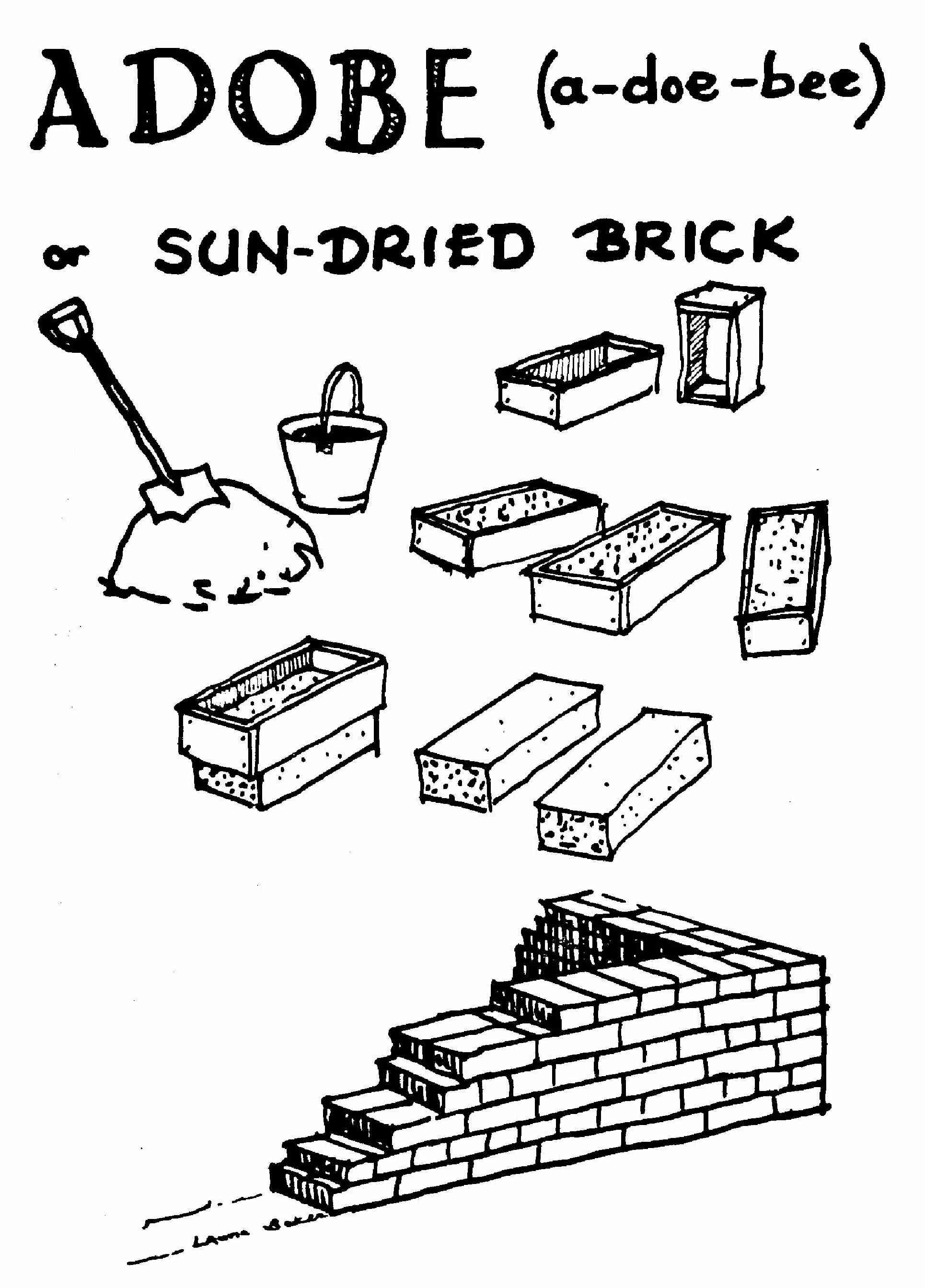

2. Re-using Mud as Adobe

Adobe is the second technique which involves masonry using sun dried bricks made out of mud. In terms of re-usability, mud stands a class higher in comparison to most other building materials as it just involves adding water to make it moldable again. To further increase its binding ability and also to make it insect repellant, stabilizers like lime, cement, etc. were added.

3. Re-using Mud as Plaster and Mortar

Mud was also used non-structurally in the form of plasters and mortar with or without stabilizers, as the idea of making it moldable again remained the same.

4. Re-using Mangalore tiles for Roof

Next in line, we have terracotta which are basically rocks artificially made out of mud. While mud goes back into the soil, terracotta doesn’t as we end up changing its chemistry altogether in the process of baking it. This enables terracotta to be a permanent building material. Hence, it was just a matter of cleaning the Mangalore tiles in order to reuse them.

5. Re-using Mangalore tiles as Filler material in slab

Apart from roofing, Mangalore tiles along with earthen pots were used as filler materials for slabs which not only helped in saving the material, but added to the aesthetics as well.

6. Re-using Bricks in Rat-Trap Bond Walls

Baked bricks too have the potential to be permanent building materials as they are also terracotta products. But unlike roofing tiles, salvaging bricks become tricky as they are bound with mortar, more so when the mortar has cement. In the interest of reducing consumption, Rat-Trap bond pattern is used which results in 20-25% material savings.

7. Re-using Wood as Rafters and Purlins

Traditional Kerala buildings are characterized by their pitched roofs. In Abraham’s Oor, wooden members as old as 300 years were salvaged for construction. These wooden roofing members dictated the design of the upcoming structure. Care was taken to choose the right type of wood for the right function.

8. Re-using Wood as Eave boards

9. Re-using Wood in Staircases and Ceiling plates

10. Re-using Wood in Brackets and Flooring

11. Re-using Wood in Furniture

12. Re-using Wood for Railings and Switch boards

13. Re-using Laterite Blocks

Laterization of soil is a process that is observed in many parts of Kerala abutting the Western Ghats. This natural phenomenon allows us to cut and excavate the soil to make building blocks and use them directly for construction. These blocks are quite large in size and cuboidal in shape but are slightly uneven in dimensions. The salvaging process here is similar to salvaging baked bricks, and thick mortar is used to adjust levels of these uneven blocks.

14. Using Boulders

Lastly we have boulders, which are generally discarded in factories due to their curvilinear profile and smooth finish. This quality makes it less preferable for construction when compared to building-quality stones. In Abraham’s Oor, boulders were bought at a cheaper price and used along with other building-quality stones, to avoid any compromise on the structural strength and durability.

With all these possibilities of using salvaged building materials for construction, there were also instances where new materials had to be used. But even in such instances, local materials and materials with less embodied energy were preferred. Connecting this with what we started with, the project stayed true to its core principles of environmental consciousness and reducing consumption throughout the whole process of construction. Abraham’s Oor possibly sets an example to the whole architecture community on how buildings of the future can be built. In the light of climate change, where we’ve come to realize that linear models of consumption don’t work anymore, the project embraces a cyclic model of consumption and passes the torch to younger generations who will hopefully take these ideas forward.

In its capacity as an NGO, COSTFORD primarily seeks to change the social, economic, and political position of the marginalized and disadvantageous groups in society. To this end, COSTFORD draws on the expertise and experience of a spectrum of talent in serving in an advocacy capacity relating to societal challenges, helping empower poor communities, conducting research and development activities, assisting with local level development and planning, promoting the transfer of appropriate technology, assisting with human resource development, conducting studies relating to a range of societal concerns, disseminating information, and serving in a consultancy capacity.

About the Author:

Kaushik Shrinivas is a practicing architect based in Chennai. He worked at COSTFORD and Laurie Baker Centre where he developed an inclination towards environment conscious architecture. On a project to make Thrissur district child-friendly, he worked with UNICEF, KILA, District Collectorate and COSTFORD to develop child-friendly design models for anganwadis and schools. He was recognised as the ‘Best Architecture Student of the Year’ by JK AYA and was a runner up in NIASA. He likes to share stories, teach, travel and express through graphic design.